Academic Humanitarians

Written by Geoff Gehman, Illustrated by Emiliano Ponzi

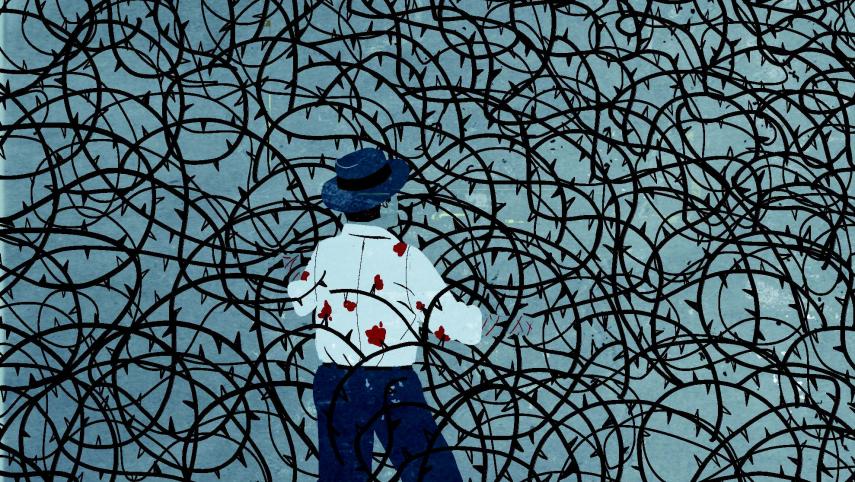

Mother Nature has decimated the educational systems of Haiti, Chile and Pakistan. But other global crises are just as devastating. Here, Lehigh researchers share their experiences as “academic humanitarians” intent on changing the odds for communities torn apart by culture, politics, tradition and war.

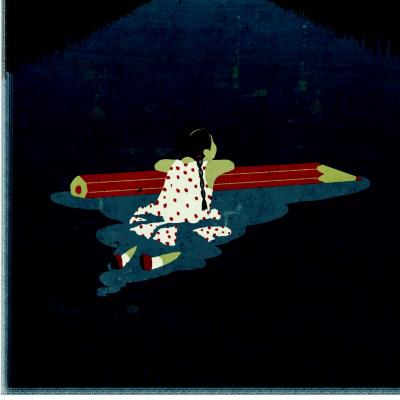

On a crowded and squalid street in a Dhaka suburb, a school founded by a Scottish church gives street girls a new perspective on life, one that transcends poverty, illiteracy and the misery of forced marriage. Here, in a few small rooms of a hostel, these Bangladeshi children learn to read and write in two languages, including English, and study science and math. They learn a profitable, respectable trade like embroidering greeting cards.

Their teachers are former street girls themselves, saved from a sorry and unremarkable life sorting rags, breaking bricks and waiting to be cast off by their parents as teen brides and financial liabilities.

This unlikely escape from traditional Bangladeshi cultural norms is called “Meider Jonno Asha,” or “Hope for Girls,” and has been studied extensively by Jill Sperandio, an associate professor in Lehigh’s educational leadership program and an authority on mentoring female students and teachers in Bangladesh. Her favorite success story is Selina, who entered the hostel school as an illiterate 14-year-old messenger for a squatters’ market. Now in her early 20s, Selina tutors youngsters in English and supervises the sale of embroidered greeting cards. She supports the school, her parents and her siblings’ education. Over six years, Sperandio has watched her friend become a confident role model for non-formal peer education.

Sperandio belongs to a Lehigh crew of scholarly rescue workers who aid schools held hostage by everything from tribal corruption to HIV/AIDS, civil war to cyclone. These teachers and teaching graduate students do much more than write papers about educational challenges, conflicts and crises. They counsel, comfort, propose lesson plans, set strategies, send books, send medical supplies, pay tuition, and help kids spell their names for the first time.

They are academic humanitarians, the College of Education’s version of the Peace Corps.

SINGLE-SEX EDUCATION IN BANGLADESH AND UGANDA

SINGLE-SEX EDUCATION IN BANGLADESH AND UGANDA

Sperandio has roamed the globe as a public servant. A native of England, she taught English and geography in Uganda and served as principal of international academies in the Netherlands, Tanzania and Azerbaijan; at the latter, she helped launch preschool and community-service programs.

Today she evaluates the training of female educational leaders in Bangladesh, where female illiteracy or semi-literacy is alarmingly high, even in free schools.

Still, Sperandio has reasons to be optimistic. The Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC) has created an innovative and unconventional system of rural schools, each with one room and each serving only one gender. Teachers are married, respectable women nominated by villagers. Each student has the same primary teacher for three to four years. Class sizes are in the low 20s—noticeably manageable and humane in a nation of more than 160 million. Flexible class hours allow students to work and raise money for families who rely on their income.

Sperandio lists the benefits of the BRAC system, which is funded largely by international patrons. Female students learn better when they’re taught by familiar females. Female teachers feel more powerful when they’re endorsed by village elders; in fact, they’re more likely to seek promotion to principal or school owner.

“They suddenly have a purpose; it gives them status in the village,” says Sperandio. “They’re part of a social revolution.”

The BRAC system has also been adopted by educational co-ops in Uganda, where Sperandio has analyzed the effects of policy changes on girls in secondary schools. Local courses with local teachers please parents who are reluctant to send their daughters to distant boarding schools, where, far from their communities, young women might be ridiculed in class by male students and teachers. And they can be victimized by male taxi drivers who trade fares for sexual acts, a sordid exchange known as the Sugar Daddy Syndrome. Sperandio believes that education is a crucial kind of affirmative action for Ugandan women, who have traditionally been dismissed as property and who only recently earned the legal right to buy property.

ISLAMIC LAW AND GENDER SEGREGATION IN SAUDI ARABIA

Islamic law and patriarchal tribal customs give women second-class status in Saudi Arabia, another corner of the world plagued by educational conflict. They are required to veil their faces, have a male guardian and socialize with the opposite sex only at home. They have limited access to advanced courses in math, science and engineering, one of the reasons they are rarely hired for high-level jobs by Saudi-owned companies. Even female leaders of the Ministry of Education, some with doctorates from co-ed Western

Institutions, can’t share offices, classrooms or school entrances with male colleagues. They can only survey a school when there are no males on the premises.

Gender segregation in Saudi schools is a specialty of associate professor Alexander Wiseman, who has consulted with the country’s Ministry of Education. The coordinator of Lehigh’s comparative and international education program, Wiseman first encountered the quirks of this policy firsthand when he led a workshop in the Saudi city of Riyadh. His topic was the use of an international study of math and science tests and trends; his audience was Ministry of Education officials. The men sat in his room. The women sat in another room and watched him on a video screen.

“If they had a question for me, they had to make some kind of noise,” says Wiseman. “It was very disjointed, and very distracting. For us, separate is not equal, although it took us a long time to reach that conclusion. For [Saudi Arabians], separate can be equal.”

Wiseman notes that gender segregation in Saudi schools has some unexpected virtues. Female test scores and employment expectations are higher, even though females are unlikely to hold well-paying, pivotal positions as mathematicians, doctors or engineers. And more women attend university, partly because they consider education a better alternative than marriage or menial work.

Last year, Saudi women received two educational windfalls. King Abdullah appointed Norah Al-Faiz as deputy minister for women’s education, the country’s first female cabinet-level official. He also opened the University of Science and Technology, the country’s first co-ed campus.

Saudi Arabia has other educational challenges unrelated to gender. It’s one of the world’s richest nations, thanks to its oil supply, yet some of its academic infrastructure is in serious need of oiling. Wiseman recalls a colleague, a Ministry of Education leader and a fellow graduate of a Penn State University’s doctoral program, who coordinated computer upgrades for 25 schools for girls and 25 schools for boys. There were only two problems. One, students weren’t adequately prepared for the technological changes. And, two, neither were the teachers.

THE IMPACT OF HIV/AIDS IN SOUTH AFRICA

The need for better teacher development programs has been a common thread in countries where education remains a work in progress, says Wiseman. He and Sperandio have traveled to South Africa to explore education in a Western Cape slum long afflicted by poverty and racial segregation.

Since 1995, the recent host of soccer's World Cup has ranked last among participating nations in international math and science test scores. Wiseman and Sperandio have proposed supplementary Saturday sessions aimed at training teachers to help primary schoolers study science more efficiently and effectively (see page 26).

Poor test scores in South Africa are a dilemma. Disease, on the other hand, is a disaster. The country reportedly has the world’s largest number of people with HIV/AIDS: the country’s Human Sciences Research Council estimates that nearly 11 percent of citizens are infected. Wiseman reports that HIV/AIDS education for primary-school girls is practically non-existent.

The lack of information about the need to use condoms and receive regular blood tests is catastrophic considering that nearly half the youngsters claim they’ve had a sexual experience by the end of seventh grade. Also at risk are secondary-school girls who pay for tuition through rather desperate means, as well as teachers who miss days of school after they become sick or become the caregivers for sick members of their family or community.

Wiseman and Sperandio have recommended programs of teacher mentoring, cognitive development and general emergency intervention to combat these ongoing problems.

CIVIL STRIFE AND THE LOST GENERATION OF LIBERIA

Schools are under siege in Liberia, a West African republic reeling from civil wars started in 1989 and 1999. Tina Richardson, associate professor of counseling psychology, is helping teachers and administrators at the University of Liberia deal with severe mental-health problems triggered by violence and shock. Health officials, she points out, have a difficult time helping teachers who can’t cope with students traumatized by war and years of repressive regimes and an aggressive military. Educators struggle to reach students less interested in learning than earning a living and being entertained. Major distractions range from delivering goods on motor scooters to supporting their extended families—whatever it takes to survive in a country just now getting on equal footing.

Richardson plans to train Liberian educators with colleague Arnold Spokane, professor of counseling psychology. The goal, she says, is to help teachers help students set goals and eliminate barriers, a process called motivational interviewing. “Teachers have to learn how to be sensitive to the nature of their students’ traumas,” says Richardson.

“They have to be taught how to understand the issues of loss; they have to be more compassionate. And administrators have to be aware that teachers are traumatized too, that they may have lost their families to the civil war as well.”

Richardson is a more personal public servant in Ghana, a West African democracy more peaceful and stable than Liberia. She’s steered Ghanan students to colleges in the greater Lehigh Valley, Pa. She’s paid for a year of tuition for students at Ghanan primary schools. She works with Women Ventures International, which lends money to Ghanan women whose businesses employ women, support families and benefit communities. She intends to improve her leadership campaign in Africa with information from her 2009-2010 fellowship from the American Council on Education.

CRISES THAT PACK A PUNCH IN THE UNITED STATES

Richardson, an American Council on Education (ACE) Fellow, is also familiar with domestic educational crises. Supported by the U.S. Department of Justice, she offered lessons in child development to police officers stationed at persistently dangerous public schools in Philadelphia, Pa. According to Richardson, cops need to remember that some adolescent defiance is natural, doesn’t necessarily equal juvenile delinquency and often doesn’t require excessive force.

Richardson is one of several College of Education teachers who troubleshoot both in the United States and abroad. Sperandio has trained women of color to lead primarily black public schools in Philadelphia where, as in Uganda and Bangladesh, students tend to learn better from teachers from similar backgrounds. Wiseman introduced Western educational traditions at a New Mexico high school attended mostly by Navajos. He enforced the lessons of textbooks and standardized tests as an English teacher and a basketball coach.

Spokane is an expert on stateside disasters. In 2005-2006, he traveled to Mississippi to help citizens and agencies affected by Hurricane Katrina. He counseled residents of cruise-ship shelters who didn’t want to return to temporary housing on shore. He comforted evacuees who returned to their destroyed homes for the first time. He debriefed mental-health professionals who lost their residences. At times he became less a psychologist and more a rescue worker: he found lactose-free baby formula on the back of a drugstore truck, an oxygen device for a child with sickle cell anemia.

Spokane was stunned by Katrina’s wrath. It wasn’t just the enormity of the devastation; rather, it was the inadequate online training he received from the federal government. The poor preparation compelled him to create Mental Health First Response, a week-long summer course in psychological first aid for victims of disasters. In 2008, he took Lehigh students to Mississippi, where they participated in a dry walling class to restore a hurricane-damaged house. He’s proud to say he’s found a new calling in his seventh decade.

TEACHING ENGLISH LANGUAGE SKILLS IN KUWAIT

Missionary work is natural for teachers at international schools who are enrolled in graduate courses run by Lehigh’s Office of International Programs. Consider the case of Ilene Winokur ’08G, a doctoral candidate in international educational leadership. She directs the intensive English program for the American University of the Middle East in Kuwait, the homeland of her husband, a pathologist for a government hospital.

One of her challenges is convincing students to speak English outside class, where they usually speak their native Arabic. Winokur encourages the youngsters to practice their second language while reading online articles and books. “If we don’t catch their attention during those 20 hours a week we have them,” she says, “we lose them.”

Some teachers at international schools in Kuwait encourage students to write argumentative essays on such sensitive subjects as capital punishment or textbook depictions of human reproduction. Winokur herself gently leads debates on the battle between Palestinian and Israeli extremists. “You can talk about the conflict,” she says, “but you can’t be seen supporting one side or the other.”

THE INTERSECTION OF TECHNOLOGY AND CENSORSHIP IN MYANMAR

Censorship is an occasional obstacle for Jacqueline Lonergan, a master’s student in international counseling and a guidance counselor in Yangon, the capital of the Union of Myanmar, formerly Burma. One of her frustrations is an Internet controlled by the government, a military junta with

the neutral, rather pastoral title of State Peace and Development Council. In 2007, the council slowed down the Web, largely to punish council protestors. Denied online access, Lonergan couldn’t complete a three-hour multiple-choice exam. Even an IT expert at the U.S. consulate in Yangon couldn’t help her pick the cyber lock.

In 2008, Lonergan began traveling to Bangkok for a reliable Internet connection. She e-mailed a paper from her friend’s apartment the day before Myanmar was hit by a cyclone that left more than 200,000 dead or missing. She insists the Myanmar government failed to give citizens adequate warning of the catastrophe. CNN, she points out, does a much better job of disaster coverage.

There are many barriers at Lonergan’s Yangon International School, a seven-year-old K-12 institution with nearly 230 students, most of them Myanmar. Her pupils rely heavily on Internet research because there are no public libraries. Because there are no credit cards or ATMs, they can’t afford college-entrance exams. This year, Lonergan

shelled out $160 for eight students to take SATs; she was repaid with the crisp, fresh American bills favored throughout Myanmar. Her patronage aided Khin Maung Latt, who was admitted to Lehigh’s Class of 2014 with a sizable scholarship.

Lonergan is a civil-rights warrior. When she taught social studies, she refused to remove from a textbook a picture of democratic dissident Aung San Suu Kyi, who has been under house arrest since 1989 for loudly opposing the Burmese government. A former Peace Corps worker in Iran, she teaches English to Buddhist monks in Myanmar, members of a sect that led the 2007 anti-government rallies.

POLITICAL TURMOIL IN MADAGASCAR AND KENYA

POLITICAL TURMOIL IN MADAGASCAR AND KENYA

Political turmoil and tribal conflict are among the hurdles faced by Pilar Starkey ’10G, a doctoral student in international educational leadership and a former principal of an American school in Madagascar, an island nation off of Africa’s east coast. In 2009 she closed her institution several times to protect students from guns fired by supporters of dueling presidents.

The same year, she was evacuated along with other U.S. citizens, her second evacuation in seven years due to the threat of political violence. She imposed a measure of order by establishing a virtual school that allowed her K-12 students to complete the year’s studies in and out of Madagascar.

In 2009, Starkey moved to Kenya with her husband, a regional safety and security officer for the Peace Corps. She began teaching English and social studies at an international school in Nairobi. She admits she struggles to make sense of Nairobi, a rich contemporary city of high-rises and malls with poor traditional society "struggling with post-colonialism, angst, horrific corruption and intense tribalism.” She encountered a residue of this anxiety when a maintenance man at her school refused to change the sign on her door because he was worried he would be fired by school leaders, who belong to a majority tribe. Starkey took his screwdriver and changed the sign herself.

Last year, Starkey took educational matters into her own hands by starting an integrated, interactive class in English and social studies. Students discussed such delicate topics as apartheid and Nelson Mandela’s debt to the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. They lived for a week with the Maasai, a semi-nomadic tribe renowned for their fierce independence and lion hunting. They raised money to buy school uniforms for slum children so they could receive free education.

A GLOBAL VILLAGE COMES TO LEHIGH UNIVERSITY

Starkey and Lonergan are among more than 250 students in over 60 countries enrolled in graduate courses sponsored by Lehigh’s Office of International Programs. This global village is supervised by a Middle East veteran. Executive Director Daphne Hobson, who founded the office in 2000, directed a kindergarten enrichment program for a state-owned oil company in Saudi Arabia, where her husband worked in public affairs.

Hobson has monitored all kinds of overseas challenges, conflicts and crises over the decade. There have been threats of terrorism at Middle Eastern branches of American schools that were established in the early ’60s to promote democracy. There have been teachers escorted by armed guards from home to school in Pakistan, a bull’s eye of sectarian violence. There have been time-zone hassles in South America, strikes in France, coups in the Congo.

Every now and then Hobson does double duty as an emergency supply officer. She burns CDs of reading lists and lesson plans for foreign students denied online access to them. She mails textbooks to teachers who overseas schools can’t afford the volumes or who can’t afford to pay exorbitant customs fees for them. (According to Hobson’s office, some governments are more likely to permit shipments from a university rather than an individual.) Relief work, she adds, is all part of helping students complete their international programs within the required six years, and making Lehigh more of a vital global satellite.

Every year, Hobson hosts two-month summer sessions for international graduate students in Iacocca Hall, the mountaintop home of the College of Education. It’s a chance to swap lessons about social justice and global citizenship. It’s also a chance to be inspired by global citizens and social-justice crusaders.

There’s Spokane, who sent three boxes of mental-health books to the University of Liberia, which has no department of psychology. There’s Richardson, who sends coloring books to help Liberian youngsters recover from losing their families. And there’s Sperandio, who had a memorable meeting with a South African boy who couldn’t spell his name after a year of schooling.

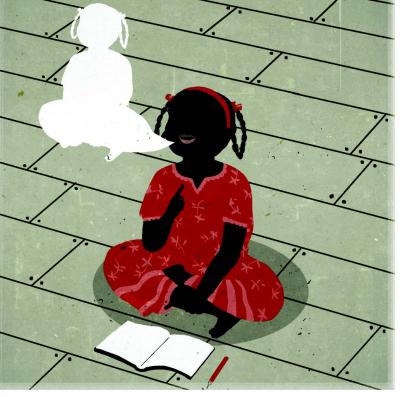

Sperandio went to Amstelhof, South Africa, to teach leadership to West Cape teachers at the request of a Lehigh alumnus. She was immediately drawn to a sad child from a squatters’ settlement. Dihago wore tattered sneakers too large for his feet. His arms were thin from malnourishment. He smelled so bad, his teacher warned Sperandio to keep her distance. Ignoring the warning, she sat down with Dihago and after five attempts, helped him finally nail his name. Classmates cheered the victory, which made Dihago beam like a beacon. Alas, he couldn’t duplicate his success after recess, which reminded Sperandio that she’s no miracle worker.

The next day Sperandio visited a soup kitchen for squatters’ children. She felt an embrace, looked down and saw Dihago wrapped around her legs. His hair was still unwashed, but his smile was still cleansing. And she remembered that sometimes a disadvantaged child's best advantage is the smallest gesture of help, the tiniest measure of hope.