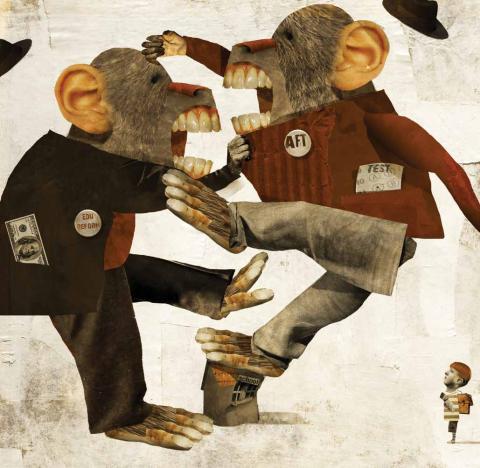

Teacher Union Wars

A newly minted New York City math teacher in 1953, Albert Shanker earned $2,600 for the year – $23,200 in today’s dollars. He could have made more washing cars.

Shanker would go on to organize the United Federation of Teachers and become one of most innovative and controversial union leaders of his time as president of the American Federation of Teachers for 23 years. He was galvanized to work for collective bargaining rights not just by the low wages but also by the working conditions. Principals ruled schools, sometimes as their own personal fiefdoms, routinely requiring teachers to give up lunch breaks to supervise recess or sit through endless afterschool meetings.

Fast forward five decades. New York City teachers deemed by administrators as unfit for the classroom sat in “rubber rooms,” or reassignment centers, where they read or did puzzles while collecting full salaries and waiting sometimes for years for their cases to be re- solved. The reassignment centers were estimated to cost taxpayers $65 million a year.

The rubber rooms became symbols of everything education reformers say is wrong with public schools.

They begged the question: Has the pendulum swung too far? Have unions, which elevated a beleaguered profession, become obstacles to improving education? Do unions protect bad teachers and hold students and communities hostage to their demands?

Welcome to the teachers union wars. On one side are education reformers, including groups backed by heirs to the WalMart fortune and other super wealthy Americans. Those reformers argue that unions and teacher tenure stand in the way of removing incompetent teachers and providing more choices for families seeking better educations for their children. On the other side are two of the biggest unions in America and their allies who say the reformers are ultimately seeking to dismantle the public school system and privatize education.

For decades, the 3-million-member National Education Association and the 1.6-million- member American Federation of Teachers have been huge contributors to mostly Democratic candidates and have usually been able to count on the party’s support in the political arena. But unions haven’t been happy with the Obama administration’s Race to the Top program, and more recently, some well-known Democrats have joined the reformers’ cause. Former Obama White House press secretary Robert Gibbs and high-profile lawyer David Boies are among those signing on with former CNN host Campbell Brown’s efforts to challenge teacher tenure in court. Unions also appear to be losing ground in the battle for public opinion. In 1976, a Gallup poll found that 38 percent of Americans thought unionization of teachers had hurt the quality of public education. In 2011, that figure rose to 47 percent.

Teachers complain the high-stakes testing regimen borne of the No Child Left Behind law has narrowed the curriculum. Now they are facing the use of those test scores in job evaluations. Meanwhile, charter schools lure away students and siphon off revenue, leaving school districts with what some say are harder-to-teach populations and less money to do it.

Unions are playing a lot of defense. But the NEA’s new president, Lily Eskelsen Garcia, is pushing back against what she calls “factory school reform” in which standardized test scores are the barometer used to judge all schools and demoralized teachers are cowed into teaching to the test.

Unions are playing a lot of defense. But the NEA’s new president, Lily Eskelsen Garcia, is pushing back against what she calls “factory school reform” in which standardized test scores are the barometer used to judge all schools and demoralized teachers are cowed into teaching to the test.

“The revolution I want is ‘proceed until apprehended,’ Garcia told The Washington Post. “Don’t you dare let someone tell you not to do that Shakespeare play because it’s not on the achievement tests. Whether they [reformers] have sinister motives or misguided honest motives, we should say, ‘We are not going to listen to you anymore. We are going to do what’s right.’”

Garcia sees the attacks on unions as part of a larger agenda by wealthy backers of the reform groups: “If they can get rid of unions, then there is nothing in their way from privatizing public schools.” She hopes to win more public support by demonstrating that teachers unions are working for better schools, not just job protection and higher salaries.

A former Utah Teacher of the Year, Garcia first turned to activism in an effort to reduce class sizes in Utah schools after she was assigned a sixth-grade class with 39 students. When she became president of Utah’s NEA affiliate, she worked successfully with a Republican governor to fund more teachers to keep class sizes down. Garcia says she has seen the difference it makes to children when they get personal attention, even if it can’t be measured by standardized tests.

But some reformers see unions as part of the problem, not architects of solutions to educational ills. They say unions and tenure laws make it extremely difficult to fire ineffective teachers. The New York State School Boards Association looked at 11 years of teacher termination proceedings and found that it costs about $313,000 and an average of 830 days to get rid of one teacher. Reports from California showed that the Los Angeles Unified School District spent $3.5 million trying to fire just seven teachers deemed incompetent, an amount that included paying the teachers full salary and benefits during the process.

Terry Moe, a Stanford University political science professor and author of “Special Interest: Teachers Unions and America’s Public Schools,” says the problem is that unions protect bad teachers. “Because they are so effective, principals know that and they’re just not going to get involved in that,” Moe says. “What they do is they try to get them transferred so they wind up in somebody else’s school… In education, they have a term for that. It’s called the ‘Dance of the Lemons.'”

Even when districts are willing to spend the money and time, they don’t always get the desired result, according to Reshma Singh, executive director of Campbell Brown’s group, Partnership for Educational Justice.

“A principal could spend three years documenting these charges, so the teacher could have hundreds of students along the way,” Singh says. “Then you could have a dismissal process that takes two years, and in the end of it, it may not even have the outcome that the district was hoping for despite all of the evidence that was collected showing ineffectiveness.”

Reform advocates won a victory in June when Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge Rolf M. Treu found that the California teacher tenure and seniority system was unconstitutional. In Vergara v. California, Treu ruled for the plaintiffs who argued that the current system makes it too difficult to remove incompetent teachers and results in poorer schools with a high percentage of low-income children ending up with more bad teachers. The judge said the system violates the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment.

The Treu decision is being appealed, and both sides agree that it is by no means the last word on teacher tenure. Singh’s group is backing a similar lawsuit, Wright v. New York.

Union representatives say that where there are problems with the dismissal process, they have worked to fix them. New York City worked with the UFT and New York State United Teachers to place time limits on the process and end the rubber rooms.

Alice O’Brien of the NEA Office of General Counsel said her union doesn’t provide lawyers for teachers convicted of a crime against a student. Of cases where they do provide legal assistance, more than 90 percent “are resolved without even going to a hearing and for very little cost.”

Barbara Goodman, communications director for the Pennsylvania branch of the American Federation of Teachers, said if a teacher is accused of harming kids, he or she can be removed from a classroom immediately. They will have due process rights but the investigation will go on without them in the classroom.

“People have a right to defend themselves, until proven guilty,” Goodman says. “And that is the American system. Should the process be dragged out? No. If it’s a bad process, fix the process, don’t get rid of the union.”

Goodman and NEA representatives say many weak teachers are “counseled out” of the profession by their peers and administrators.

Richard Kahlenberg, a senior fellow at The Century Foundation, a progressive think tank, says some school districts, such as in Toledo, Ohio, and Montgomery County, Maryland, have found success in instituting a peer assistance and review process. Kahlenberg described the rise of the Toledo program in the 1980s in his biography of Albert Shanker, “Tough Liberal.”

Richard Kahlenberg, a senior fellow at The Century Foundation, a progressive think tank, says some school districts, such as in Toledo, Ohio, and Montgomery County, Maryland, have found success in instituting a peer assistance and review process. Kahlenberg described the rise of the Toledo program in the 1980s in his biography of Albert Shanker, “Tough Liberal.”

“Expert teachers come into a school and try to help struggling teachers improve their craft,” he says. “And if it turns out the assistance isn’t working, then the teachers recommend that their peers be terminated. In places like Montgomery County, Maryland, the number of teachers that are fired or terminated through that mechanism is much greater than in the past when principals were in charge of deciding whose employment was terminated.”

But Kahlenberg and unions point out that retaining good teachers is also a problem. Research shows nearly 50 percent of new teachers leave the profession within the first five years.

Teacher retention is one reason why unions have an uneasy relationship with Teach for America. Founded in 1990, TFA recruits new college graduates, including many non-education majors, gives them five weeks of training and places them in mostly poor inner city schools. Many of those schools are charters and only 12 percent of charters are unionized. Some TFA teachers continue to teach after their two-year commitment is up, but many do not. By five years, only about 15 percent remain at those schools – which is a higher attrition rate than teachers who go through regular teaching certification.

Union critics like Moe and Singh also bemoan a seniority system that forces districts to let go of newer teachers first when budget cuts force layoffs. “If you were doing it based on what’s best for kids, you would keep the most productive teachers, the very best teachers, and you would lay off the worst teachers,” Moe says. “But that’s not what happens. The unions insist on seniority and in the case of layoffs, it’s the youngest, lowest seniority teachers who get laid off even if some of those teachers are the very best in the district.”

But in such cases, how do you decide who is best? Unions argue that basing teacher quality on student standardized test scores is a seriously flawed way of determining good and bad teachers.

Murky Research Results

The research on whether unionization and collective bargaining help or harm students is a mixed bag, partly because it is difficult to isolate the effect of unions on student achievement. “My reading of the research is that our difficulties with raising achievement have very little to do with – or anything to do with – teachers unions,” Kahlenberg says.

In 2002, Robert Carini of Indiana University Bloomington did a review of 17 studies on the effects of unions on student achievement and found that the preponderance of methodologically rigorous studies showed increased student achievement for average students in unionized schools. “At the same time, a union presence was harmful for the very lowest- and highest-achieving students,” Carini wrote.

Meanwhile, Moe says the best studies were done by Caroline Hoxby in 1996 in the Quarterly Journal of Economics, himself in 2009 in the American Journal of Political Science and Katharine Strunk in 2011 in the journal Education Finance and Policy. All three show negative effects from unionization.

Still, unions argue that if they are bad for students, why do states with strong unions like Massachusetts and New Jersey consistently have higher test scores than Right to Work states like Mississippi and Alabama?

It’s complicated, Moe says, pointing out that Mississippi has a history of segregation and is one of the poorest states. “Part of the reason Massachusetts scores so well is it has among the highest per capita income in the whole country and it has very low levels of minorities compared to states like Mississippi,” he says. “Those are the big factors right there.”

Of course poverty is a factor in how well students do generally on standardized tests, unions say, which is why it’s unfair to tie test scores to teacher evaluations or pay. While poverty is a significant problem, it can’t be an excuse to avoid improving the quality of teachers in low-income areas, reformers say. “I just don’t think we can afford to wait until we have fixed poverty to fix schools,” Singh says.

"If they can get rid of unions, then there is nothing in their way from privatizing public schools."

Lily Eskelsen Garcia, National Education Association

The New Orleans Experiment

In August 2005, Hurricane Katrina swept away much of New Orleans, including its largely unionized, low-achieving public schools. They were replaced by a wave of mostly non-unionized charter schools.

Some education reformers saw this as a near perfect experiment for determining whether unions have a positive or negative effect on learning. Overall, test scores have been rising, but in the city’s Recovery School District they are still considerably lower than the Louisiana average.

Some skeptics say New Orleans is not the ideal Petri dish for the union/non-union experiment because the before-and-after student population is not the same and neither is the spending per pupil. Many students did not return after Katrina, and charter schools receive funding from philanthropies as well as taxpayer money.

Unions and their allies say a better gauge of the effectiveness of mostly non-union charter schools is how they rate nationwide, compared to traditional public schools. There are some terrific charter schools that consistently boast of high student achievement, but on average, charters don’t outscore regular public schools.

Changing Economy

So if there is a war against teachers unions, why is it happening now? According to Kahlenberg, it has to do with the changing nature of the U.S. economy.

“To our credit, our society is really trying for the first time to educate students from all backgrounds to high levels,” he says. “For years we didn’t need to do that because we had a lot of blue collar jobs that did not require people to have high levels of education. You could effectively write off large chunks of society and still have a functioning economy, and that’s no longer true.

“We really need to tap into the talents of all of our students so the stakes are higher than ever before. As a result there are new efforts to try to improve education for students from all types of backgrounds, and it’s proving incredibly difficult. And when you’re in a frustrating situation, it’s tempting to look for scapegoats, and so the teachers unions are an easy one.”