School Shooters - Inside Their Minds

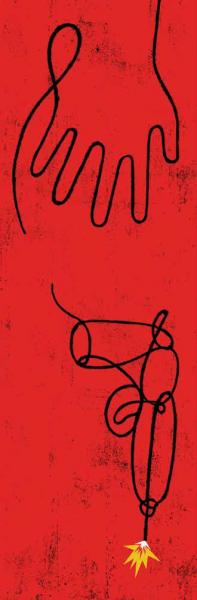

Written by Elizabeth Shimer Bowers | Illustrated by Edel Rodriguez

At the request of Theory to Practice, alumnus Peter Langman—a sought-after expert on the psychology of young people who commit rampage school shootings—recently sat down with one of his former professors in Lehigh’s College of Education, Professor of Counseling Psychology Arnold Spokane, whose research also touches on violence in schools.

Their conversation uncovered some fascinating insights on the individuals who conduct school shootings as well as what teachers, administrators, parents, and students can do to help prevent these tragedies. The following is an edited version of their discussion.

Q: The Bureau of Justice Statistics reports that in 2011, approximately 1 percent of students aged 12 to 18 reported being the victim of violence at school. For serious violence, it is one tenth of 1 percent. Does the public perception of the prevalence of violence in schools match the reality?

Q: The Bureau of Justice Statistics reports that in 2011, approximately 1 percent of students aged 12 to 18 reported being the victim of violence at school. For serious violence, it is one tenth of 1 percent. Does the public perception of the prevalence of violence in schools match the reality?

Peter Langman (PL): First of all, we have to define what you mean by school violence. Some people would include bullying. My focus is on the large-scale school shootings. I can talk about that. There is also the whole issue of gang violence. In terms of school-related homicides, those are down significantly. In fact, violent crime in general has gone down over the last 20 years in the U.S. However, that is not people’s perception, so I think that is where the media comes into play.

Also what comes into play is the fact that even when school-related homicides are going down, when they do occur, it seems like they are occurring en masse. It is not just one kid shooting another kid or stabbing another kid. It is the large-scale rampage attacks that gets the media’s attention.

In terms of numbers, school shootings are such a rare phenomenon. Most of us will not see a school shooting in our lifetime. Someone once put together statistics on secondary school shootings, and you would have to be at that school for like 6,000 years before you would see a school shooting. That is how rare they are.

Q: What are some of the factors that lead kids to reach the point of becoming violent in school? And is it a slow build, or do they just snap?

PL: Generally, it is a long, slow build. They don’t tend to snap as people talk about it—“He’s a nice kid, I guess he snapped.” You don’t just wake up one day and become a mass murderer.

What I outline in my book—Why Kids Kill: Inside the Minds of School Shooters—is three distinct types of people who commit school shootings. I think that is important to understand because they come from different backgrounds, and they do what they do for different reasons.

The three types are the traumatized shooter, the psychopathic shooter, and the psychotic shooter.

The traumatized shooters—they come from dysfunctional families, poverty, abuse in the home, a number of them were sexually abused outside the home, parents are poor, kids bounce around between mom to dad to grandma, sometimes they are in and out of foster care, there is no stability. And eventually, the rage and depression build.

The other two types come from essentially stable and intact families. One type is the psychopathic, someone who is narcissistic, doesn’t care about other people, no empathy, no remorse, no respect for laws and regulations or authority, they are going to do what they feel like doing. They are often sadistic, so they get a thrill over having the power over life and death.

Arnold Spokane (AS): Are these psychopathic shooters isolated?

PL: They don’t typically have a real strong social group. They may have some friends and they may have some followers. Some of them are fairly isolated.

But when you are talking about isolated, the third group is the psychotic group. This group is under the schizophrenia spectrum and some of them are very isolated. Take Seung-Hui Cho at Virginia Tech. He didn’t have a friend. He didn’t speak to anyone in four years of college. He was an extreme loner. Adam Lanza at Sandy Hook [Elementary School in Newtown, Conn., where 20 children and six adult staff members were shot to death in December 2012] spent most of his time in his mother’s basement playing videogames and watching movies. He was very isolated. So when you see that extreme isolation, this is usually with the psychotic shooters. They are having hallucinations, they hear voices talking to them, paranoid delusions, delusions of grandeur.

Going back to your question about slow build or do they snap, people may be evolving into schizophrenia over a period of years. There often is a series of events shortly before the attack that pushes them over. What you see is there is some kind of an event, or they are rejected by a girl. They get in trouble at school—it may be a minor thing, but there is some kind of conflict with the school. Sometimes they get into trouble with the law, sometimes drugs or alcohol. So you see one thing on top of another thing on top of another thing, and it is building and building and building. And often they talk to their friends about school shootings, maybe about their own plans. Sometimes these friends are supportive, or they don’t say, ‘No you can’t do that’ or tell an adult, so there is a sense, ‘It is OK with my friends—they don’t object to it,’ and if they do object, they may say ‘I was just kidding—I would never do that.’ But really, they are planning and it builds and builds. There is often peer encouragement of some kind. Sometimes the shooters have role models for violence. They look at Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold at Columbine High School as a role model or Charles Manson or Hitler. They get into various ideologies that would support violence as appropriate. There are a lot of things coming together.

But you don’t have an ordinary kid who wakes up one day and becomes a mass murderer.

Q: What’s the role of media, and videogames, movies, and television programs?

PL: There is the media as in the news media, and then there is violent media as in films and so on. Some kids will tell you after the fact that they were very much influenced by something in the media. For example, [Eric] Harris and [Dylan]

Klebold from Columbine, the code name for their attack was NBK, which is Natural Born Killers. They loved the movie and watched it so many times they could essentially recite the dialogue. Another kid, Jamie Rouse, said after he saw Natural Born Killers that it made killing look fun, it made killing look easy.

When you talk about videogames or violent films, on the one hand, millions of kids and adults play violent videogames and watch violent movies and never pick up a gun. But there are a few kids who are already at risk, who may be close to the edge, who find sometimes inspiration in violent media.

AS: Relatively speaking, school shootings are very infrequent acts. And we don’t have enough evidence yet to know which perpetrator is going to actually wind up doing something, so it is very difficult to assess or predict who will actually go through with a shooting and who will not. There may be a large number of kids, who will fit that description but who won’t do it so that is the trick—to try to figure out who will do it.

Q: Regarding school violence, what should teachers and administrators be on the lookout for in terms of red flags?

PL: When you talk about warning signs, there are a couple of key things. One is attack-related behavior. This means anything a kid or an adult is doing that indicates he or she is planning an attack. And that could be stockpiling weapons, researching other shooters, recruiting a friend to join the attack, or it could be warning a friend to stay away from school that day.

The latter things fall under a category called leakage—when people leak their intentions. So secondary school shooters often leave quite a trail, they often talk about their plans with their friends and encourage them to join them. And if those kids were trained on those warning signs, they’d know they’d better tell someone.

The latter things fall under a category called leakage—when people leak their intentions. So secondary school shooters often leave quite a trail, they often talk about their plans with their friends and encourage them to join them. And if those kids were trained on those warning signs, they’d know they’d better tell someone.

And if schools were trained on how to recognize threats, they could prevent that attack. Sometimes kids are so obsessed with another shooter that they model themselves after that kid, quote them on their website, etc. In a couple of cases, they have even made pilgrimages to the places where those shootings occurred. For example, in 2006 a kid named Alvaro Castillo lived in Hillsborough, N.C., and he was obsessed with Columbine. In fact, he tried to commit suicide on the seventh anniversary of Columbine. His father came home and stopped him. He was psychotic. He decided God had spared his life for a higher purpose, which was to commit a Columbine-type attack. He lived in North Carolina and convinced his mother to drive him to Littleton, Col., where he videotaped from the car scenes of Columbine High School. They drove by the house Eric Harris had lived in. While he was out there, he bought a black trench coat just like Harris wore. He was obviously obsessed with Harris and Klebold and Columbine. And a few months after his attempted suicide on the anniversary of Columbine, he committed a small-scale shooting [after shooting and killing his father]. Fortunately, he didn’t do too much damage. But his mom obviously knew he was obsessed with Harris and Klebold. He was in love with his gun, named his gun, slept with his gun; his gun was his best friend at the time. So you have an obsession with firearms, obsession with Columbine, mental instability—a lot of warning signs.

Q: Overall, what are some of the most important things teachers and administrators can do to help prevent violence in schools?

PL: Schools need to have threat assessment procedures—multidisciplinary teams within the school, trained on threat assessment. Right now at the secondary school level, the focus is on lockdown procedures. That is what you do when there is an armed intruder in the building. That is a little late. Lockdown procedures are going to minimize the damage; they won’t prevent an attack. The idea of threat assessment is you look for the warning signs that lead you to the attack-related behavior, you identify the risk before someone ends up with a gun in the school. And that means training the students, too, because if anyone knows who’s planning something, it is most likely the other kids, and they need to be trained. For example, if you see this or hear this, this is what you do and why you do it. And even if it is your friend who you think will be mad at you, if you don’t tell anyone, your friend is probably going to be dead or in jail for the rest of his or her life. You may be dead, your other friends may be dead, and you are going to have to live with that. So kids need to be guided through and maybe given some role-plays and scenarios. They need to think through the ramifications.

In addition, teachers need to be trained in warning signs they may see that other people wouldn’t. There are kids who have written stories about kids killing other kids at school and handed them in as school assignments. A few weeks later they do exactly what they wrote about in their papers.

When Cho was in high school, Columbine occurred, and he wrote a paper in favor of Columbine. Virginia Tech didn’t know that, but when he was at Virginia Tech, he wrote a paper about a guy named Bud who was planning a school shooting. Bud ended up not doing it, but there was an interdepartmental email from Virginia Tech where one of his professors told colleagues, ‘Every assignment he had handed in has been about shooting people.’ So teachers may see suspicious school assignments. Harris and Klebold made a video in their video production class called “Hit Men for Hire,” where a kid was being picked on, and he hired Klebold to come in and shoot people.

AS: Do you have any advice to students coming into the College of Education on how to conceptualize problems with violence in schools and school safety and education broadly for children?

PL: A few thoughts come to mind. The first is, avoid reductionist thinking. So much of the material on school shooters points to a single cause or a single explanation. The kid was bullied. Well, millions of kids are bullied in this country and maybe one in ten million becomes a school shooter. He may have been bullied, and he may not have been. In some cases, maybe he was the bully. Or people blame the media. He watched Natural Born Killers. Yes, but so did millions of others. There is a tendency to focus on one cause, but you have to think very broadly. That may have been a factor, maybe he was bullied. Or he was obsessed with the videogame Doom. But why was he obsessed with Doom? What did that do for him as a person, why was he drawn to it? What was the family life like? Was there a lot of rejection? Was he using drugs? What of a dozen or more different factors came together to cause him to do this?

AS: In other words, look at a child’s context deeply and broadly and not superficially. Know these kids.

PL: Yes.

AS: There is a phenomenon that occurs, I’m not sure how often, but someone will have an inkling or small thought or feeling that a student is in trouble or something is wrong, but they will gloss over it. And I think it is important in the training to trust those suspicions or small feelings and not just dismiss them. Rather, take some action and find out whether that is a kid who is in trouble and whether there needs to be something done to respond to it.

PL: If you read 10,000 papers in your career, and suddenly you read one and you start getting nervous, pay attention to that.

AS: Even a student’s behavior that seems out of line. We are psychologists, but even as professors and trainers, we may see things, and they may hit as almost a subconscious feeling about someone. You may act on it, or you may just forget about it and go on about your business. I think the tendency to go on about your business is a mistake now, and I think monitoring behavior and recognizing it as suspicious is very critical.

I think it is hard for teachers and school personnel when their ratio [of students] is so high. Now with cutbacks with the economy, collateral personnel are now being withdrawn, and that is the wrong way to go. It means fewer eyes on the classroom.

What we need is more people looking, more people checking their instincts for what might be going wrong and then acting on those instincts to try to prevent them. Instead, I don’t think the economics we are dealing with is backing that up. Instead, we are having fewer eyes on the classroom, fewer eyes on the school and neighborhood.

And there is very good evidence that the more monitoring you have of any environment, the safer that environment is.