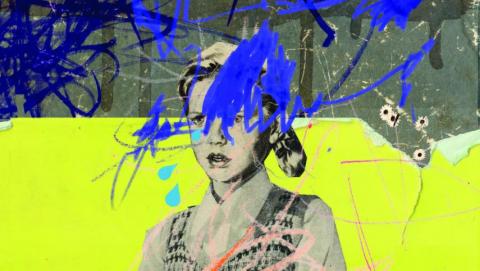

School Bullying

Mia* is in fourth grade. Sometimes, a girl in her class, Sophie, would make fun of her. Then one day, Sophie brought invitations to her birthday party to school. She handed them out to everyone in her class. Everyone, that is, except for Mia.

Every day for what seemed like weeks, Mia watched as the girls sat together at lunch and played together at recess, always talking about the party.

As the only child in the class not going to the party, Mia was increasingly excluded. Soon, she started having trouble sleeping and she didn’t feel like eating. She stopped wanting to come to school, and her performance when she was in the classroom dropped.

Finally, things started to change. Trainers from a local organization that fights bullying started an educational program at her school. Through this program, Mia says she “realized that bullying happens to lots of kids every day, and really nice kids too.”

With her new understanding of bullying, Mia confronted Sophie and asked her how she would feel if she were similarly excluded. Mia also started speaking with her friends again. With the behavior out in the open, Sophie stopped bullying Mia and the environment in the classroom began to improve.

Before Mia entered the anti-bullying program, she didn’t understand that Sophie was bullying her. That’s because many people think that bullying is simply physical aggression. But the aggression can also be verbal, or it can be relational, like that experienced by Mia.

“The technical definition of bullying is an unidirectional, unprovoked abuse of power,” says Roberta Heydenberk, an adjunct professor in the College of Education’s teaching, learning and technology program. Roberta and her husband, Warren Heydenberk, an emeritus/adjunct professor at the college, have been studying bullying and conflict resolution for nearly 20 years.

They have found that bullying is astonishingly common: Nearly 30 percent of children have been bullied, and three-quarters have experienced attempted bullying. All this aggression takes a toll. Bullying decreases the subjective well-being, or happiness, of victims. These students have difficulty focusing and don’t feel a strong sense of attachment to school.

BUT THE IMPACT OF BULLYING GOES BEYOND THE VICTIMS

“Bullies don’t have a good future,” says Warren Heydenberk. “They have all the correlates of delinquency, alcohol abuse, suicide, a whole gamut of problems you don’t want to see.”

The Heydenberks’ most recent research shows that the people who benefit the most by reduced bullying are the people who witness the activity—the bystanders. This means that while roughly 30 percent of children are bullied, nearly everybody in the school suffers from its side effects.

“Bullying erodes the whole school-based community,” says Warren Heydenberk. “Kids get shut down; they don’t want to go to school. But bullying is like air pollution. If you can open the windows and clear it out, all the kids are better.”

“Bullies don’t have a good future. They have all the correlates of delinquency, alcohol abuse, suicide, a whole gamut of problems you don’t want to see.”

Dr. Warren Heydenberk

WALKING IN ANOTHER’S SHOES

The Heydenberks’ goal is to clear out that pollution. Roberta Heydenberk is the research director at the Peace Center, an organization in Langhorne, Pa., that promotes community peace and social justice through programs that help reduce violence and conflict in our schools.

The Peace Center runs the bullying prevention program that gave Mia the power to confront her bully. The program uses interactive exercises to raise awareness of bullying, increase communication, build empathy and teach children to think before acting. The program is integrated into the school curriculum and facilitated by trained peace educators.

“We try to get children to step into the shoes of the other person,” says Barbara Simmons, the executive director of the Peace Center. “This work shows them how their words can hurt or lift other people.”

One of the Peace Center’s success stories is Jacob. Every morning, when students arrived in his classroom, Jacob would stand in the doorway. He wouldn’t let the students pass until he had insulted each one.

After observing this, the peace educator asked Jacob to sit next to her and help her with the program. That day, the children were doing an activity called “The Torn Heart” that uses a beautifully decorated paper heart to illustrate the damaging power of words.

The peace educator reads a story about bullying, and every time the main character is put down, a student volunteer rips the heart. The children can hear the paper rip with each insult, and they can see how it looks.

AS HE RIPPED THE HEART, JACOB BEGAN TO CRY

“If you asked that boy what bullying is before the program, he would not have said he was bullying. He would have said he was teasing,” says Marianne Elias-Turner, the program director at the Peace Center.

“Through the activity, he saw that he was tearing his classmates’ hearts. He was trying to connect, but he had no language to do it.”

Jacob ended up apologizing to the class for his actions.

"We’re raising future citizens here. Isn’t it imperative that we teach them character as well? Teachers say they can’t take one more thing on the plate, but this is the plate.”

Barbara Simmons, Executive Director, Peace Center

THE CLASSROOM AS A FAMILY

The Heydenberks’ research shows that comprehensive conflict resolution programs, like those run by the Peace Center, boost students’ academic achievement and moral reasoning.

These programs teach students skills like listening and stopping to think before acting. When these strategies are embedded in the curriculum and practiced throughout the day, students learn how to recognize, express and manage their emotions, and how to solve conflicts.

All of this creates a better learning environment and increases school attachment. And if students feel like they’re part of something enjoyable, they are more willing to go to school, and they perform better academically.

To see how effective the Peace Center’s work is, one only has to visit Deborah Walker’s second-grade classroom at Willow Dale Elementary School in Warminster, Pa. Walker first contacted the center almost 20 years ago, and she has been integrating conflict resolution and character education into her curriculum ever since. She has seen discipline problems drop and academic performance increase as a result.

"We’re raising future citizens here,” says Walker. “Isn’t it imperative that we teach them character as well? Teachers say they can’t take one more thing on the plate, but this is the plate,” she adds. “It holds the curriculum together.”

Walker makes principles like respect and empathy part of every lesson. For example, when her students read a story about baseball legend Jackie Robinson, they examine the actions of all the characters for lessons about good behavior.

“Even fractions are fair,” she laughs. “What you do to the numerator, you do to the denominator.”

Because these principles are part of every lesson they learn, the students in Walker’s class understand how to stop bullying. They don’t pick on other children, and they have the strength to stand up to people who pick on them. And through the common language of the program, the class has become a tight-knit community.

The students feel the difference. For example, take Anna, who moved to Pennsylvania from Ukraine. When she was in first grade, children in her class excluded her and made her feel unwelcome.

“Last year, there were people bullying me,” she says. “This year, I didn’t want to go to school on the first day because I was scared it would happen again. But it didn’t happen. There are no kids that bully here in this class, so I like this class. We’re like a family.” .

*All of the children’s names have been changed to protect their privacy.

HOW CAN YOU COMBAT BULLYING IN YOUR SCHOOL?

Roberta and Warren Heydenberk have been studying bullying and conflict resolution for more than 20 years.

Here are some tips that teachers and administrators can use to reduce bullying in their schools.

Watch your own attitude.

“The attitude of the teacher about bullying is the strongest predictor of whether there’s going to be bullying in a class.room,” says Roberta Heydenberk. Remember that bullying isn’t just physical. More often, especially as children get older, it’s verbal.

Make a social contract.

At the beginning of each school year, work with students to develop a social contract that outlines how classmates want to be treated and how they will treat each other. Stu.dents are more likely to follow the contract if they write it.

Check in with each other.

The Heydenberks’ research has shown that the most effective way to reduce bullying is to begin each day by going around the room and having students check in with a brief “I statement” of how they feel. This takes just minutes and builds a culture of community in the classroom.

Ask the bully, not the victim.

“One of the classic mistakes is to ask the victim what happened. But the victim is almost always re-victimized, because then they’ve been a snitch,” says Roberta Heydenberk. Instead, ask the bully to tell you what happened.